Holes / Hydraulics

Holes (AKA: Souse Holes, Hydraulics) are caused by a depression in the river bed like water flowing over a boulder. Water cascades over the boulder (or ledge) forcefully downstream and water from downstream flows back upstream to fill in the depression. We often refer to holes as Smiles or Frowns. If the ends are out flowing downstream (Frown), you can exit the hole on either end. If the ends are facing upstream (Smile), exiting the hole isn't as easy. Upstream ended holes typically have a jet stream underwater that you can catch with your paddle or body to forcefully pull you down and out. A perfectly uniform hole - straight across like one formed by a dam can be very difficult to escape and often requires assistance. Smaller holes are often used like eddies by advanced paddlers. Play boaters (and squirt boaters) love holes as this feature enables the many tricks they like to perform. Notice the picture of Big Nasty on the Cheat River.

Holes (AKA: Souse Holes, Hydraulics) are caused by a depression in the river bed like water flowing over a boulder. Water cascades over the boulder (or ledge) forcefully downstream and water from downstream flows back upstream to fill in the depression. We often refer to holes as Smiles or Frowns. If the ends are out flowing downstream (Frown), you can exit the hole on either end. If the ends are facing upstream (Smile), exiting the hole isn't as easy. Upstream ended holes typically have a jet stream underwater that you can catch with your paddle or body to forcefully pull you down and out. A perfectly uniform hole - straight across like one formed by a dam can be very difficult to escape and often requires assistance. Smaller holes are often used like eddies by advanced paddlers. Play boaters (and squirt boaters) love holes as this feature enables the many tricks they like to perform. Notice the picture of Big Nasty on the Cheat River.

Play boaters absolutely love holes. This feature is where they can perform most of their tricks. Anyone venturing into class IV whitewater needs to be very comfortable surfing holes (just like class III boaters need solid boat reading skills, eddy turns, and ferry skills). The following video is excellent at describing basic hole surfing technique: Basic Hole Surfing Technique.

One type of hole we ALWAYS stay away from are those created by low head dams. These manmade structures create a perfectly uniform hole that you can't escape from. The backwash is often many yards downstream and very powerful - even motor boats are helpless once caught in the backwash. The following video is well worth watching to understand why these types of dams are so dangerous: Low Head Dam Video.

Rocks / Pillows

Another river feature you will certainly encounter is a pillow. This feature is caused by water piling up on a boulder. As with all rocks, you generally lean towards them to lift the upstream edge of your boat out of the water. Here is an excellent example from the Gauley called Pillow Rock.

Another river feature you will certainly encounter is a pillow. This feature is caused by water piling up on a boulder. As with all rocks, you generally lean towards them to lift the upstream edge of your boat out of the water. Here is an excellent example from the Gauley called Pillow Rock.

Rocks come in all shapes and sizes. Most of the time, we try to avoid rocks. When rocks have a large flat profile to the current, we can afford to get closer to them and plant a low brace on the pressure wave edging the downstream side of our boat down and towards the rock wall. Large rocks that have a narrow profile typically don't build up a pressure wave. We need to either avoid contact or run a foot or two to the side - especially if there is a large hole below. The water runs fast alongside the rock forming an eddy line. Aiming for the downstream bottom of the rock on a 45° angle with some speed will make it easy to catch the eddy behind the rock. In the picture on the right, you can see a very clearly defined eddy behind the midstream rock.

Rocks come in all shapes and sizes. Most of the time, we try to avoid rocks. When rocks have a large flat profile to the current, we can afford to get closer to them and plant a low brace on the pressure wave edging the downstream side of our boat down and towards the rock wall. Large rocks that have a narrow profile typically don't build up a pressure wave. We need to either avoid contact or run a foot or two to the side - especially if there is a large hole below. The water runs fast alongside the rock forming an eddy line. Aiming for the downstream bottom of the rock on a 45° angle with some speed will make it easy to catch the eddy behind the rock. In the picture on the right, you can see a very clearly defined eddy behind the midstream rock.

Strainers & Sieves

Strainers are a very common site on small streams that recently had a great deal of rain. When creeking, we always keep an eye out for them and typically get to shore ASAP when we see one unless there is an easy line around the obstruction. Sieves are far less common and are usually well documented in the river database on the AW site. My advice is don't mess with sieves. Stay away from them or portage if you have to.

Strainers

Strainers are usually downed trees or a collection of branches and trash. Do whatever you can to avoid these death traps. If you accidentally swim into a strainer, work very hard to climb up on the structure rather than getting impaled or strained by hidden limbs. Here is an example of one on the Savage River in Maryland. In the SWR class, we always perform a strainer swimming drill: Strainer Swimming Drill. This is one place where the defensive swimming technique will fail and you will be swept under. If you can't avoid a strained, swim head first and quickly towards the strainer. When you reach the strainer, push yourself over the branch and kick your feet to help push you over.

Strainers are usually downed trees or a collection of branches and trash. Do whatever you can to avoid these death traps. If you accidentally swim into a strainer, work very hard to climb up on the structure rather than getting impaled or strained by hidden limbs. Here is an example of one on the Savage River in Maryland. In the SWR class, we always perform a strainer swimming drill: Strainer Swimming Drill. This is one place where the defensive swimming technique will fail and you will be swept under. If you can't avoid a strained, swim head first and quickly towards the strainer. When you reach the strainer, push yourself over the branch and kick your feet to help push you over.

Sieves

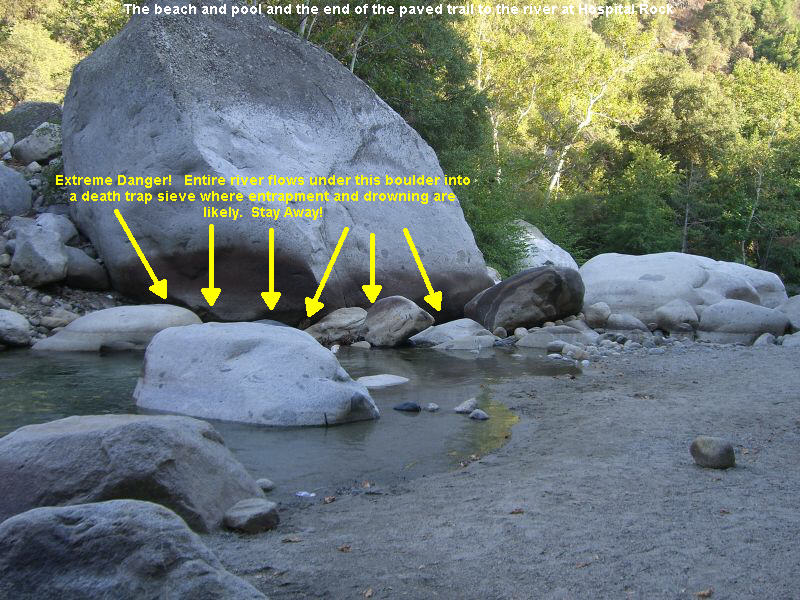

A great way to think of a sieve to to think about how a toilet bowl works when you flush it. They are formed by cracks in rocks that often get backfilled with another small rock that gets lodged in tight. Water pours through this hole and anything else that is unfortunately to be close by. Never take chances with a sieve - stay away! AW does a great job at providing warnings for known sieves in rapids. Here is a great explanation on what a sieve is from Initiation Rapid on the Upper Gauley: Sieve.

A great way to think of a sieve to to think about how a toilet bowl works when you flush it. They are formed by cracks in rocks that often get backfilled with another small rock that gets lodged in tight. Water pours through this hole and anything else that is unfortunately to be close by. Never take chances with a sieve - stay away! AW does a great job at providing warnings for known sieves in rapids. Here is a great explanation on what a sieve is from Initiation Rapid on the Upper Gauley: Sieve.

Ledges / Horizon Lines

Large ledges typically have a distinct horizon line that precedes them. You can often identify a large ledge by looking at trees below, listening for the loud sound of crashing water, or watching the boater in front of you suddenly disappear. You may encounter ledges in class II on up rapids. A great class II ledge in our area is Snap Falls on Muddy Creek - see picture on the right. On smaller ledges, boaters below will identify when it is safe to run by holding their paddle vertically. On more challenging ledges or those with potential dangers, we typically set suitable safety. When running ledges, avoid the "Old School" habit of holding the paddle shaft above your head and leaning way back. This takes your paddle out of the safe zone - the paddlers box. Leaning on the back of your boat also makes the boat less stable when you land. A better approach is to enter with a little bit of extra speed, plant a very strong last stroke at the lip, and try to lift the front of your boat with both knees. This maneuver definitely takes some practice.

Large ledges typically have a distinct horizon line that precedes them. You can often identify a large ledge by looking at trees below, listening for the loud sound of crashing water, or watching the boater in front of you suddenly disappear. You may encounter ledges in class II on up rapids. A great class II ledge in our area is Snap Falls on Muddy Creek - see picture on the right. On smaller ledges, boaters below will identify when it is safe to run by holding their paddle vertically. On more challenging ledges or those with potential dangers, we typically set suitable safety. When running ledges, avoid the "Old School" habit of holding the paddle shaft above your head and leaning way back. This takes your paddle out of the safe zone - the paddlers box. Leaning on the back of your boat also makes the boat less stable when you land. A better approach is to enter with a little bit of extra speed, plant a very strong last stroke at the lip, and try to lift the front of your boat with both knees. This maneuver definitely takes some practice.

Waterfalls are really tall ledges. Some are relatively easy to run like Wonder Falls on the Lower Big Sandy. Many others have difficult entrance rapids and shallow landing areas you need to avoid like Great Falls on the Potomac. At the bottom of many falls are upstream and downstream hydraulics centered on the curtain of the falls. Many falls cut into the ledge that forms them and this creates a pocket of air behind them. When considering running a falls, make certain you know where to land and it is deep enough. Depending on the height of the falls, you may wish to land flat (short falls or shallow landing - aka a boof move) or angled entry for tall falls. Notice the example of Great Falls on the Potomac in the picture on the right.

Waterfalls are really tall ledges. Some are relatively easy to run like Wonder Falls on the Lower Big Sandy. Many others have difficult entrance rapids and shallow landing areas you need to avoid like Great Falls on the Potomac. At the bottom of many falls are upstream and downstream hydraulics centered on the curtain of the falls. Many falls cut into the ledge that forms them and this creates a pocket of air behind them. When considering running a falls, make certain you know where to land and it is deep enough. Depending on the height of the falls, you may wish to land flat (short falls or shallow landing - aka a boof move) or angled entry for tall falls. Notice the example of Great Falls on the Potomac in the picture on the right.

A horizon line often denotes the beginning of a steep drop or ledge, notice the example in the right side picture. If the rapid is known to be safe, I like to cautiously paddle to the middle of the river to get a better look. You can use your back ferry or draw strokes to move laterally to line up for the best position to start the drop. If you can find an eddy close to the ledge, go catch it and get a better look from your boat.

A horizon line often denotes the beginning of a steep drop or ledge, notice the example in the right side picture. If the rapid is known to be safe, I like to cautiously paddle to the middle of the river to get a better look. You can use your back ferry or draw strokes to move laterally to line up for the best position to start the drop. If you can find an eddy close to the ledge, go catch it and get a better look from your boat.

Page 2 of 6